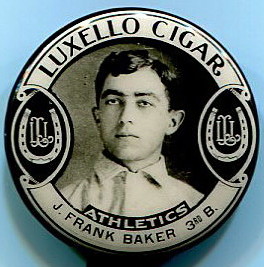

In my younger days I collected pinbacks of every sport. Nothing was off-limits. I was fascinated by sports pins of all kinds, including cricket pins from Australia, hockey pins from Canada, and soccer pins from Uruguay (winner of the first World Cup). It is through them that I learned how to identify pins made outside of the United States. But my first love has always been baseball, and large PM10 pins in particular (my first pin). To be very clear, I am speaking of pins with the name on top and having a pale white background.

The first time I saw a large PM10 pin that was not of a baseball player I was uncertain of the sport. He wasn’t wearing a cap. A very logical guess (by you) as to the sport would be football or basketball. Not so. The identity of the sport and my subsequent research led me to discover that in my youth I was blind to the passionate interest this sport generated. Furthermore, growing up in Connecticut, it was all around me. I have no recollection of anything ever being reported on it in the sports section of my local paper. The pin was of an auto racer. I had never heard of the guy. All I knew with certainty was that it was a large PM10 pin, and I was determined to learn more about it. I subsequently did, which is the basis of this column. However, my goal remains the same as before: to shed some light on who might have made the large PM10 pins. More specifically, I am using the auto racing pins as a way to identify who made the baseball pins. This second part of the column on large PM10 pins brings us tantalizingly closer to answering that question. We end up with a pile of circumstantial evidence, but no proof. I hope you enjoy reading this saga as much as I did putting it together.

I begin with the premise that the reader knows as much about auto racing as I once did: nothing at all. Here is a brief primer. Auto racing comes in many forms. I will mention only three. First, there is dirt track racing. Probably all drivers began their career racing on dirt tracks. A race might consist of 30 laps around the track. Among race car fans, this is the purest form of racing at its most primal level. Second, there are hard tracks paved with asphalt or concrete. These tracks are larger, the races involve more laps, and speeds are higher. Finally, there is a type of racing based on the design of cars used in the Indianapolis 500, the most iconic of all American races. Currently the seating capacity of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway is over 250,000. The speeds get faster every year, and the cars are specially designed for this race. Appropriately enough, the name of the design is an “IndyCar” (that is not a typo—all one word with a capital C). The IndyCar drivers race in a national circuit of tracks designed to accommodate the tremendous speeds the cars reach. Cars that race on hard tracks are called “stock cars.” Cars that race on dirt tracks can be just about anything from a stock car to a midget car to a jalopy.

When you think of the legends of auto racing, as 4-time Indy 500 winner A.J. Foyt, you might think he would never “lower” himself to participating in short track racing in a stock car. Not so. After he won his first Indy 500 in 1961, he also participated in local short track racing. It would be a coup for a local track to attract a driver of the stature of Foyt. As they say, racing gets in your blood, and the drivers would pick their races by the size of the purse. In the early 1960s, at a small track the winner’s purse might be $1,500. While many drivers aspired to one day race in the Indy 500, relatively few would reach such a pinnacle. Most drivers alternated between dirt tracks and hard tracks over the course of the racing season. Today both the Indy 500 and the Coca-Cola 600 (a stock car race) in Charlotte are run on the same day. Some drivers start the day racing in Indianapolis and then fly to Charlotte to drive in the second race: 1,100 miles of racing in one day (but time flies at 200 mph).

The large PM10 pins were made of stock car racers (a few made it to the Indy 500). What we know as NASCAR today evolved from dirt racing. Legend has it that stock car racing began with moonshiners modifying their cars to out-race law enforcement officers in hot pursuit. Whatever the origin, auto racing was very popular across the nation, in both rural and urban areas. Following the finding of my first large PM10 auto racing pin, I picked up others along the way. Here are some of them:

Bobby Allison was voted one of the Top 50 racers in NASCAR history Both of his sons died in auto racing related accidents.

Junior Johnson was one of the stock car racers who began his racing by running moonshine. A North Carolina distillery sells three types of alcoholic drinks based on Johnson’s family recipe for moonshine.

Junior Johnson was one of the stock car racers who began his racing by running moonshine. A North Carolina distillery sells three types of alcoholic drinks based on Johnson’s family recipe for moonshine.

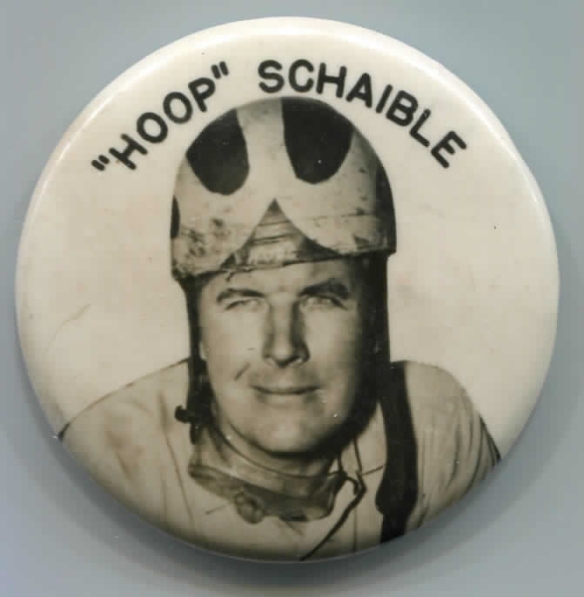

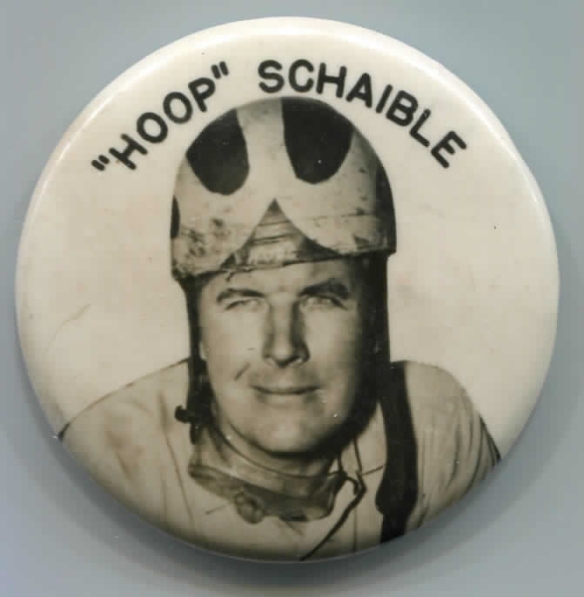

Who could not root for a guy named “Hoop”?

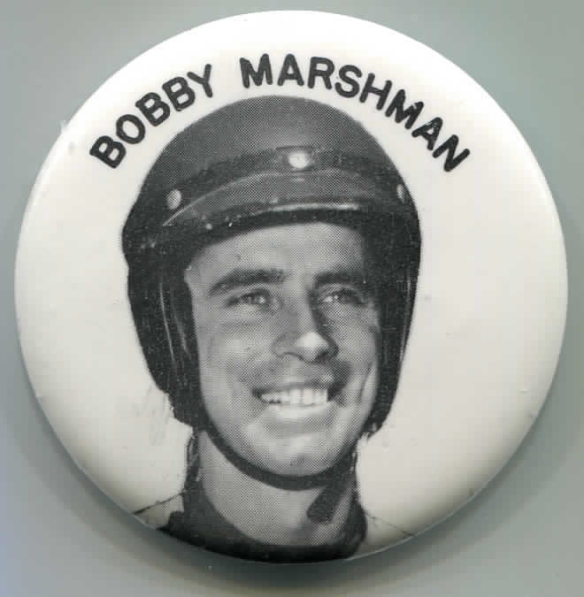

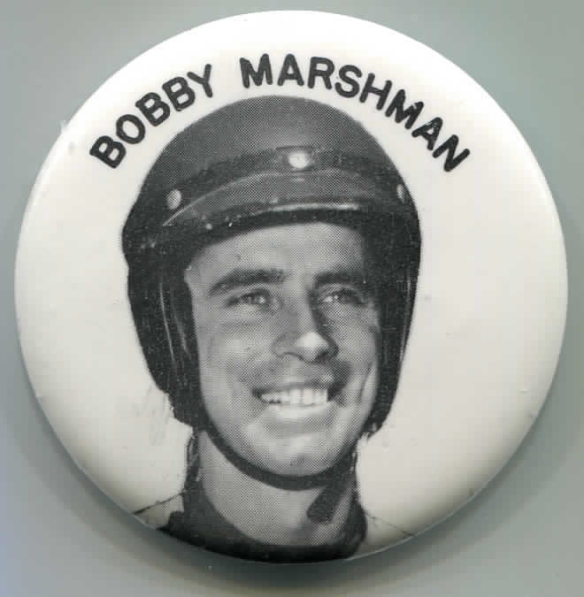

Who could not root for a guy named “Hoop”? Bobby Marshman was one of the stock car drivers who raced at the Indy 500.

Bobby Marshman was one of the stock car drivers who raced at the Indy 500.

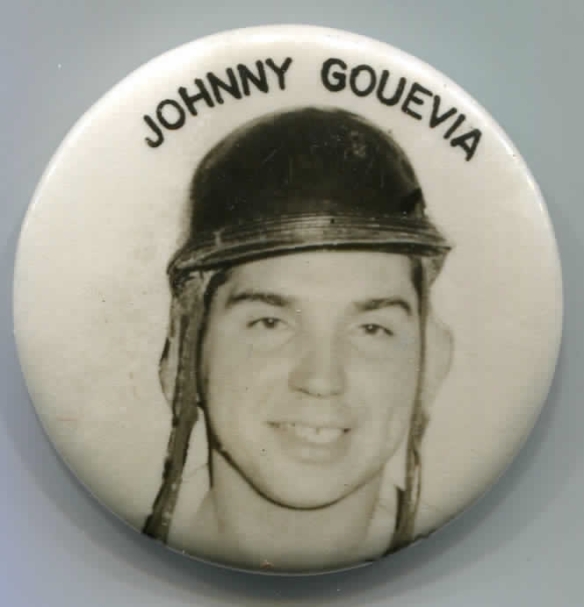

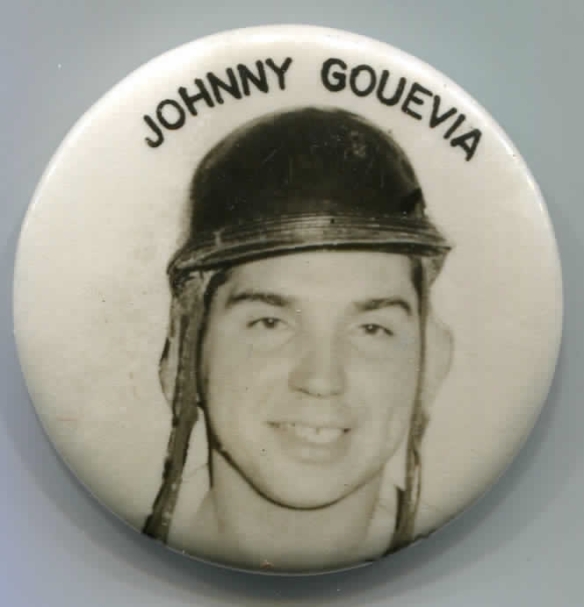

Gouevia’s helmet doesn’t look like it would provide much protection in an accident.

Gouevia’s helmet doesn’t look like it would provide much protection in an accident.

McGreevy’s pin is one of the first to include the checkered flag design.

Bud Tingelstad was the childhood hero of late night talk show host David Letterman who grew up in Indianapolis.

Bud Tingelstad was the childhood hero of late night talk show host David Letterman who grew up in Indianapolis.

These pins were among the most odd-ball of all my pins. Given their unusual size (2&1/8”) and design (head shot on a pale white background), I believed their source was the same as the large PM10 baseball pins. If you recall from Part I, I believe these pins were made in the New York or northern New Jersey area. Street vendors would place an order for a certain number of pins to be made of a certain baseball player. How many different vendors would hawk these pins outside of the three ballparks in New York? A small number, I would guess. They knew the identity of the pinmaker (individual or company) through word of mouth. It was only a short drive from the three ballparks to the likely location of the pinmaker. But how would the business model work with auto racing pins? Assuming the auto racing pins were sold the same way (at the track) as the baseball pins (at the ballpark), the points of sale to customers would be more varied. Around 1960 there were many local tracks in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut area. At first it seemed plausible to me that the same business model could be followed, but it became a stretch the more I thought about it. Consider the location of the pinmaker as a bulls-eye, and you draw concentric circles around it. At a radius of 50 miles, you would encompass at least one dozen race tracks, maybe more. So the potential market would be there, but given the product in question, it didn’t seem to make much business sense. These pins would typically sell to the public at $.25 – $.50 apiece. That would be a very thin profit margin for the vendor, considering the mileage in question and amount of traffic congestion. A 10-mile distance from the source to three markets is one thing, but up to a 50-mile distance to one market is another. It just didn’t add up to me. Still, I had no better answer.

Then, out of thin air (almost literally, cyberspace) came a series of clues that fell together. About 15 years ago someone on eBay was selling many large PM10 auto racing pins. There were about 20 individual lots. All of these pins were in mint condition; it was as if they had never seen the light of day. Amidst the pins were some design variations to the standard large PM10 pins that led to a very different interpretation as to how they were distributed. Two final pins, neither being of drivers, were absolutely critical. I cannot call them the Rosetta stones to identifying the source of the large PM10s, but close.

The following pins are among 21 that present the name of a track as well as the driver.

Blanket Hill Speedway was in Kittaning, PA (near Pittsburgh). “Hank Bauer” is the answer to the trivia question about the only baseball player to appear on a large PM10 pin in two different poses. His corresponding counterpart in auto racing is “Dave Lundy.”

Victoria Speedway was in Dunnsville, NY, near Albany (a half-mile dirt track formerly used for horse racing). The pins of Pete Corey are evidence that the name of the track was promoted as heavily as the driver.

Fonda Speedway is in Fonda, NY (near Mohawk).

Oswego Speedway is in Oswego, NY (near Syracuse).

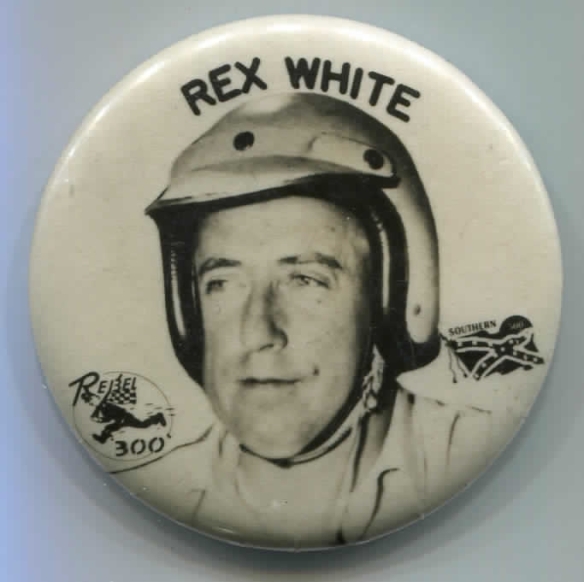

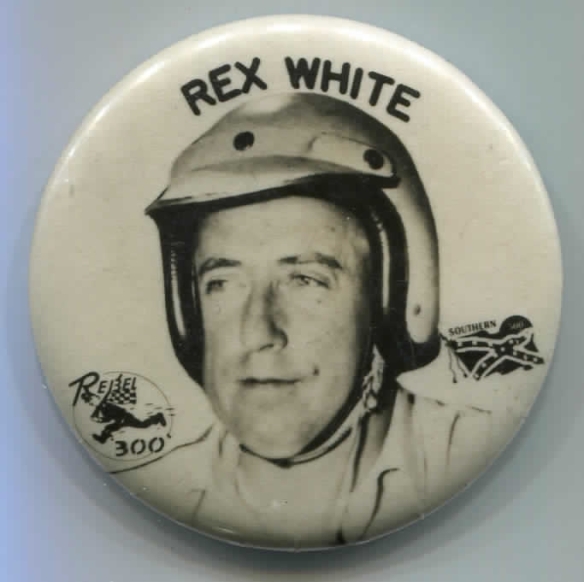

The Southern Rebel 300 was held in Darlington, SC (it is now a 500-mile race with a different name). The name of the track on this pin was not explicitly named but is inferred from the two design features.

Raceway Park was in Chicago.

Vallejo Speedway was in Vallejo, CA (near San Francisco). A pin with a “full design:” name of driver, name of track, and checkered flag feature.

Needless to say, the location of these tracks far exceed 50 miles from NYC. These pins served to completely change my understanding of all the large PM10 auto racing pins. A different business model had to be followed for their distribution and sale, but not necessarily their manufacture. While the pinmaker sold baseball pins directly to street vendors (and the vendors probably picked up the pins at his place of business), the auto racing pins were not sold to street vendors. They were most likely purchased by the owners of the tracks. The pins were shipped to the tracks, one as far away as 3,000 miles. Perhaps the earliest auto racing pins just listed the driver’s name. I believe the various track owners wanted more customized pins to promote their own tracks. The pinmaker then expanded his design offerings, adding the name of the track and also checkered flags, symbolic of racing. As such, these pins have richer designs than the very plain baseball pins of the 1950s. This is one indication the auto racing pins were made after the baseball pins. But there is also another more powerful reason. As I indicated in Part I of this column, the large PM10 baseball pins were made over an eight-year period based on the players depicted. However, all the pins were constructed identically with a spring pin. The large PM10 auto racing pins were likely made over time as well. I have a total of 42 of them. Three of them were made with the same spring pin design feature as used in all the baseball pins. As such, I believe they are the oldest of the auto racing pins, and they only present the driver’s name. The  remaining 39 pins were made with a different type of pinning mechanism. This method was developed later in the technological evolution of pinmaking. It was a more sophisticated design, using two metal plates instead of one, and the pinning mechanism is a claspback design. After the pin has been affixed to clothing, the tip of the horizontal pin is tucked under a clasp to prevent it from falling off, as well as decreasing the likelihood the wearer would get unintentionally stuck with the sharp end of a spring pin. While I offered a precise start date and end date for the large PM10 baseball pins, I do not know precisely when the auto racing pins began and ended. My best guess is they began in 1959 or 1960, and ended around 1965 or 1966 (Junior Johnson retired in 1966). Unlike baseball which is characterized by extensive and precise record keeping, there is no such analogue for auto racing. The Indy 500 race is thoroughly documented (it began in 1911). There is far less information on the early years of stock car racing, and even less on local dirt track racing. While some of the racers on the pins began their careers in the 1950s, whatever records exist on these drivers indicate that they all raced in the early to mid-1960s. For example, it is documented that Bud Tingelstad ran his first race in 1960.

remaining 39 pins were made with a different type of pinning mechanism. This method was developed later in the technological evolution of pinmaking. It was a more sophisticated design, using two metal plates instead of one, and the pinning mechanism is a claspback design. After the pin has been affixed to clothing, the tip of the horizontal pin is tucked under a clasp to prevent it from falling off, as well as decreasing the likelihood the wearer would get unintentionally stuck with the sharp end of a spring pin. While I offered a precise start date and end date for the large PM10 baseball pins, I do not know precisely when the auto racing pins began and ended. My best guess is they began in 1959 or 1960, and ended around 1965 or 1966 (Junior Johnson retired in 1966). Unlike baseball which is characterized by extensive and precise record keeping, there is no such analogue for auto racing. The Indy 500 race is thoroughly documented (it began in 1911). There is far less information on the early years of stock car racing, and even less on local dirt track racing. While some of the racers on the pins began their careers in the 1950s, whatever records exist on these drivers indicate that they all raced in the early to mid-1960s. For example, it is documented that Bud Tingelstad ran his first race in 1960.

Now comes the part of the column where I engage in a continuation of my speculative theory about the origin of the large PM10 pins. Please withhold your judgment until the end of the column. I have pieced this together from the confluence of both the baseball and auto racing pins. I will begin with an inflammatory hypothesis: the maker of the large PM10 baseball pins probably violated the law. Not the selling of unlicensed merchandise (there were no such laws at the time), but the likely non-payment of sales tax and income tax from the sale of these pins. In the 1950s the pinmaker most likely ran a cash-only business with these pins. He accepted cash (only) from the street vendors. The street vendor accepted cash (only) from fans buying the pins. Unless the street vendors kept records of pre-game and post-game inventory, there would be no way to document how much was owed in taxes. While the pinmaker might have kept more precise records than the vendors, I speculate that he did not. I doubt if either party issued receipts; the street vendors certainly didn’t. If the ultimate truth is that both the pinmaker and street vendors faithfully paid sales tax and reported the generated sales as a basis to pay income tax, I sincerely apologize for impugning the integrity of both parties.

Now jump ahead to today. Ballparks sell some items costing hundreds of dollars (e.g., a replica uniform). A beer costs $10 at Yankee Stadium. Many fans pay for these items with a credit card. There is a documented record of the sale that provides a basis for the vendor to report sales tax. Back in the 1950s, vendors did not sell anything expensive enough to warrant paying by check, and credit cards had not yet been invented (or at least they were not accepted as a form of payment at ballparks). As such, in an all-cash context, it might be argued that no one paid sales tax for anything purchased at a ballpark. Not so. I remember being at Yankee Stadium in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Beer vendors would walk the aisles. A case of Ballantine beer was placed in a rectangular metal tray that the vendor carried in front of him with the aid of a strap that ran behind the vendor’s neck, attached to both sides of the metal tray.

[This paragraph has nothing to do with pinback buttons. It is based on a fond memory. The beer vendor carried a can opener. It had a wooden or metal handle and at the end of it was a sharp piece of metal in the shape of the letter V. This is long before the invention of “pop-top” cans. When I would watch my father open a can of beer at home, he would punch one hole in the can with the can opener, then rotate the can 180 degrees, and punch a second hole in the can. Then he would pour the beer from the can into a glass, but the beer would pour only from one hole. I asked him about the purpose of the second hole. He said it was to let the air out of the can. One day I snuck a can of beer for myself (I recall being about 15-16). I wanted to test his theory, so I punched just one hole in the can and poured the beer. Not knowing beer from shinola, I quickly saw the importance of the second hole. The beer I poured looked nothing like the beer he poured. Mine was about one inch of beer and six inches of foam. Back to the ballpark. When you ordered a beer, the vendor did not bother with rotating the can of beer in the tray. Instead, at lightning speed he used the can opener to punch 3-4 holes in the same side of the can. Then he poured the beer into a paper cup and produced hardly any foam. I asked my father why he did not also use this particular method. He replied, “Because the beer vendor is a professional.” I would enjoy hearing from any reader who remembers this era of buying beer at a ballpark.]

The beer vendor wore an unusual badge. The cost of the beer was 50 cents. The rectangular badge indicated the beer itself cost 48 cents, and 2 cents was for sales tax. Above the badge, right above the “0” in “50,” was a rectangular flap of plastic. It was attached by some sort of hinge. After the 6th inning the flap was lowered, revealing the number “5.” In short, after the 6th inning there was a nickel increase in the cost of a beer, but the price increase was not enough to warrant collecting more in sales tax. I remember my uncle, a consummate beer drinker, was most displeased with the unwarranted price jump, which he brought to my attention. So street vendors who sold pins collected no sales tax (at least not so indicated), but sales tax was overtly included in the price of beer sold by vendors in the stadium.

What does sales tax have to do with who made large PM10 pins? When the maker of large PM10 pins went from baseball to auto racing, his business model had to change. Many of the customers of the pinmaker were out of state. The owners of the tracks probably would be very reluctant to send cash through the mail, so they paid by check. Now there is a paper trail. For the tracks within the state of New Jersey (and there were many), there would be the issue of both sales tax and ultimately income tax. While the making and selling of baseball pins could be an “underground” operation because of the cash-only method of payment, the entire operation had to become “above ground” when non-cash payments were involved. But there is a huge missing link in this supply chain. How would the owners of the various race tracks around the country know the identity and address of the pinmaker? Word of mouth may suffice as a marketing method among a small group of people operating within 10 miles of each other, but it won’t suffice when your potential market is the entire nation. How does the pinmaker now “go national” in his marketing plan? There must have been a way to generate national awareness of his availability.

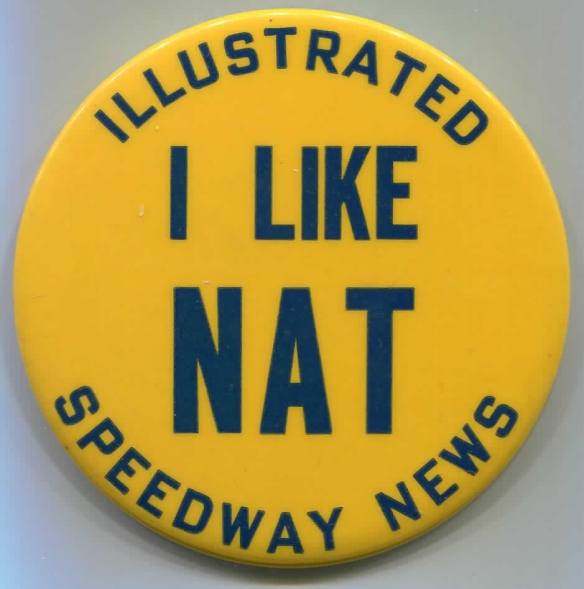

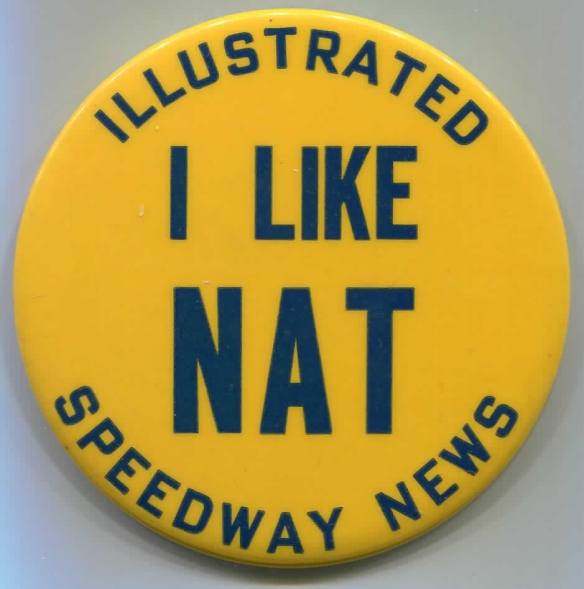

Enter the two (partial) Rosetta stone pins. I acquired these along with the mint pins of the racers. I don’t know why I did so, because they each are only tangentially related to sports. In hindsight, I’m ecstatic that I did. They helped to unravel the mystery of the large PM10 pins (or at least offer a very plausible explanation of them). The first pin is a large PM10 pin. But it is obviously not of a racer, at least not wearing his helmet. He looked like some office manager. Why was a large PM10 pin made of him? Like most of the drivers, I never heard of him either. Nat Kleinfield was both a prominent track announcer and a writer about auto racing. He lived in northern New Jersey (Fair Lawn), and was well-known for his manner of speech in calling races in various tracks in New Jersey. He also had a radio show about auto racing. The second pin makes mention of his first name, Nat. It is an expression reflecting a popular phrase of the era. “I like Nat” was a variation of President Eisenhower’s campaign slogan: “I like Ike.” The rest of the pin presents the name of some publication called “Illustrated Speedway News.” That pin led me to investigate Illustrated Speedway News (ISN). What follows next was the result of many hours of internet research.

Nat Kleinfield was neither the owner nor editor of ISN. He wrote a feature called “Speaking of Speed” and was the resident luminary columnist for ISN. ISN began in 1938. It was a weekly publication, coming out every Tuesday. The format of the newspaper was modeled after the New York Daily News. The cover page was a photograph, as was the back page. Each issue was typically 16 pages in length. ISN was regarded as the definitive publication for national auto racing news. While ISN presented itself as having a national focus on auto racing, in reality it was heavily East-coast oriented. There would be a few columns written by stringers from California and the mid-west to legitimate its proclaimed national scope, but beyond that, almost everything else was about racing news in the East. ISN contained stories about race tracks and announcements of upcoming races, mostly around the tri-state region. In reading it I learned about tracks that were operating within 30 miles of my home as a boy in Connecticut that I never knew existed. My assumption that auto racing was primarily a Southern phenomenon was completely wrong. Maybe there were more tracks in the South, but there were also many tracks in NJ, NY, CT, PA, and MA. The corporate headquarters for ISN was Brooklyn. A few issues occasionally come up for sale, but only two years of ISN have been archived on microfiche, 1964 and 1965. Fate was very kind to me regarding the years in question. My theory of the large PM10 pins is that the baseball pins stopped in 1959, and the auto racing pins came next. The issues from 1964 and 1965 could prove most useful for me.

Here was my reasoning. The maker of the large PM10 pins was from the New York or northern New Jersey area. After the Dodgers and Giants left New York, he switched from cash-only local sales to national sales for auto racing pins paid for by check. ISN was the definitive auto racing publication and was available for national distribution through subscription. How did the owners of race tracks around the nation find the pinmaker? I concluded he must have placed an ad in ISN. Furthermore, if the pinmaker who made the auto racing pins also made the baseball pins, the pinmaker’s location had to be in the New York or northern New Jersey area. I crossed my fingers and hoped to find an ad that showed a picture of a large PM10 pin that would unequivocally nail the lid on this mystery. After all, that is exactly how the mystery of the “Jackie Robinson tells his story to the Brooklyn Eagle” pin was solved, as described in a previous column. I scrolled through the pages of each issue. Many of the big ads were placed by insurance companies. In the back of each issue was a section for classified ads. While the majority of these ads were placed by individuals typically selling automobile parts, some companies placed ads as well. Ad space was sold by the vertical inch; many ads were only one-two inches.. Typically the same small ad would run for two-three weeks. However, one company ran its ad every week, the exact same wording, week after week. While the ad was not the proverbial “smoking gun” that I hoped to see, what I found was seductively taunting. The company was called “Motor Speedway Specialties Co.” The ad said they specialized in “Novelties and Souvenirs.” Furthermore, no other company consistently advertised the offering of novelties and souvenirs. As a bonus to further entice me, the ad specified “Wholesale Only.” How much more could I hope for? The grand prize was the location of this company: Irvington, NJ. For those of you unfamiliar with NJ, Irvington is three miles west of Newark. Among the inferences that can be drawn from this ad is ISN ordered its own promotional pins from one of its advertisers.

How strong is the evidence that one company made all of the large PM10 racing pins? Extremely probable, but not absolutely conclusive. They all were made with an unusual sized die, 2&1/8”. Unusual, but probably not the only die of that size ever manufactured. More conclusively, the font is the same on every pin. Furthermore, I have never seen this particular font on any other pinback in any sport. Since ISN was the only definitive national racing publication at the time (historical records indicate such), and since “novelties and souvenirs” include pinback buttons (they do, but it is not an obvious or immediate connection), and since no other racing souvenir company other than the Motor Speedway Specialties Co. consistently advertised in ISN, then the evidence is very compelling. Second, we would have to assume that if a large PM10 auto racing pin that is identical in design and structure to a large PM10 baseball pin, both types of pins came from the same source. The diameter, pale white background color, and font are identical in both. Among the PM10 baseball pins there are a few that have a font that is slightly thinner than the rest. Otherwise, the fonts on all the rest of the baseball pins are identical to every one of the auto racing pins. Just like the baseball pins, there is no union bug on any of the racing pins. This is what the scientific community would call extremely strong circumstantial evidence, but not proof. What is the weakest part of my theory? Yes, the evidence is overwhelming that the same company made both the large PM10 baseball and auto racing pins, but the mere presence of an ad for a company that makes novelties and souvenirs does not necessarily confirm that it was the actual source of the pins in question. Without a detailed invoice or a company brochure (preferably illustrated) that describes the products it sells or the verbal account of a knowledgeable person (e.g., a former employee), there is break in the final link of the chain.

When a theory is proposed, it is not uncommon to encounter some evidence that challenges the theory’s accuracy. In such a case you either have to modify the theory to accommodate the new evidence or explain the likely irrelevance of the disconfirming evidence. The second “Rosetta stone” pin has a bright yellow background, not pale white. It is also of a different diameter (3.00”) than the large PM10 of Kleinfield. The identity of the company that made this pin is on the curl: “Edmar Specialties Company, Forest Hills, NY.” Did the maker of the large PM10 pins reveal his identity through this second pin? I don’t think so, but possibly. The use of color suggests a different pinmaker, but a different diameter is even more strongly indicative of it. A company like Whitehead & Hoag made a wide array of pins, and as such they would have invested in many dies of different sizes to meet their customers’ needs. A small company that provided an array of “specialties” or “novelties,” including pinbacks, would be far more inclined to work with only one die or maybe two. Like an artist who only works in one medium (charcoal, for example), small novelty companies would likewise offer extremely limited choices in the size of a pinback and its design. Edmar offered 3.00” pins, with the option of color. Other popular sizes for pinbacks are 1.75” and 1.25”. The large PM10 pinmaker most likely limited himself to 2 & 1/8” pins with no color. Again, I can’t prove this exclusivity in design. There is no historical record of the Edmar Specialties Company in Forest Hills, NY. It was likely a mom-and-pop operation whose name was probably a hybrid of their first names, as Edward and Martha.

In my opinion the larger colorized pin is far more plausible as a promotional product for ISN than the black and white large PM10 pin of Kleinfield. In fact, the large PM10 pin of Kleinfield makes no reference at all to ISN. Why would ISN order such a plain pin in promoting its lead writer? Probably because the pinmaker made pins featuring the drivers that Kleinfield wrote about in his weekly column, “Speaking of Speed.” As such, ISN honored its lead writer with the same type of promotional item reserved for the people that he covered in racing news. The Kleinfield pin is the only known large PM10 pin that does not feature a sports figure. In my opinion the Kleinfield pin offers the biggest clue to ultimately revealing the identity of the maker. When ISN inquired about another pin that would present many words, no head shot, and be in color, the pinmaker probably said he did not produce pins of the size needed to clearly present all the words, and his pins were only in black and white. So ISN found Edmar for the second pin. Speaking somewhat loosely, I believe the black and white headshot, pale white background, distinctive diameter, and distinctive font was the “trademark design” of pins made by the Motor Speedway Specialties Company of Irvington, NJ in the 1950s and 1960s.

I conclude with a paradoxical answer to my question of whether an individual or company made the large PM10 pins. The correct answer is likely “both.” The owner of the Motor Speedway Specialties Co. may have made the baseball pins as an “under the table” operation based on cash sales to avoid taxation. When the baseball pin market subsided, he switched to auto racing pins. Because most or all of his sales were now traceable because of non-cash payments, the auto racing pins were officially made “above the table” by his company. You will have to decide for yourself what you think of all the evidence provided and inferences drawn as the basis of my conclusion.

However, my sleuthing is not over on this matter. I am in the process of trying to establish the owner of the Motor Speedway Specialties Co. through corporate records archived by the Secretary of State of the State of New Jersey. I was advised not to expect a speedy reply. But if I get a name, I will next attempt an archival recovery of his obituary. If I do, I hope it reads something like this:

“Peter Pinmaker passed away three days ago. He worked at the Whitehead & Hoag Company in Newark for 40 years. After he retired, he operated a novelties and souvenirs store in Irvington. Some of his creations brought immense pleasure to others, yet few knew the identity of their creator. He had great interest in both baseball and auto racing. He is survived by his wife, Petunia.” Even that would not nail the case shut, but it sure would seem to bring us closer, wouldn’t it?

Three closing notes. We all know the history of baseball. You may wonder what happened in auto racing. Nat Kleinfield had a stroke in mid-1964, and auto racing suffered from his diminished presence. He died in 1970 at age 60. The Daytona 500 went on to become the premier stock car race. The early years involved racing on the hard sand of Daytona Beach at low tide. Drivers who lost control of their cars either wound up in the soft sand or in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1959 a hard track was built in Daytona for what has become a famous race. The mid-late1960s brought about great social change, particularly of a counter-cultural nature. People’s changing tastes were reflected in the growing use of drugs, popular music, the hippie movement, and of course, the Vietnam War. Many long-standing civic traditions were altered, but auto racing, like baseball, continued to be part of the American social fabric. Just as many minor league baseball teams folded in this era, auto racing suffered as well. Local dirt track racing still exists, but on a much more limited basis than in its heyday. Only three of the tracks presented on the pins remain in business: Darlington Raceway, Fonda Speedway, and Oswego Speedway. The majority of the tracks that promoted their races in ISN cease to exist. Even ISN folded in the early 1970s. Stock car racing lost most of its local flavor as NASCAR found corporate sponsors and follows a national circuit of races held in huge tracks. Darlington Raceway is now part of the NASCAR circuit. The stock car auto racing industry is now highly structured and formalized. There are some small tracks that still hold races today, as Fonda Speedway and Oswego Speedway, but with reduced racing schedules. In 1969 MLB merchandise licensing laws went into effect, part of the larger process of regulating, standardizing, and formalizing professional sports in America. Long gone is the uniqueness of local and regional influences on these sports. Just as professional baseball had to change with the times, so did professional auto racing. Both sports continue to have a populist appeal and are enjoyed by millions of fans every year. The large PM10 pins of auto racers are but a remnant of a bygone era. I have 74 of the large PM10 baseball pins of this design. I have 42 large PM10 auto racing pins. If auto racing were an obscure sport, it would not have generated so many pinback buttons. Furthermore, while there may be a few large PM10 baseball pins of players on the three New York teams that have not yet turned up in the hobby, I believe there are many more large PM10 auto racing pins waiting to be discovered. Most notably, not one of my auto racing pins makes any reference to the Indy 500. Why not? I suspect it is because the Indy 500 considers itself to be better than all other races, and a small novelty store located in Irvington, NJ is beneath its standards for supplier quality. Alternatively, maybe the pinmaker didn’t have the capability to produce 10,000 pins for one order.

Second, I have one large PM10 pin that is neither of a baseball player nor an auto racer. It is of a professional wrestler who performed in the 1960s. I don’t know if its existence serves to refute or support my theory of who made these pins. By the way, I made an imprecise statement in Part I of this column. I said, “There are less than 100 known large PM10 pins.” I should have said, “There are less than 100 known large PM10 baseball pins.” I did not include the auto racing pins in that total. Assuming the pinmaker made all the large PM10 pins (2&1/8”) with the pale white background, the running total of known pins so far is 117 (74 baseball, 42 auto racing, 1 wrestling). This pinmaker has undoubtedly made more pins than any other single individual in the history of sports pinback buttons. That makes his anonymity all the more maddening. The hobby owes him a huge debt of gratitude, whomever he may be.

Finally, who besides a collector would have many large PM10 auto racing pins? Not just 1 or 2, but 20. Either a former race track owner, a former pinmaker, or someone who was sentimentally attached to them. I cannot remember the name of the person who 15 years ago put those 20 auto racing pins on eBay. These pins are in absolute mint condition. Someone had taken very good care of them. For a long time they probably resided in a box tucked away or maybe in a dresser drawer, along with other keepsakes. In putting the final touches on this column, I wanted to see if I could find anything about their possible source. I think I found it, but like everything else, I can’t prove it. I researched Nat Kleinfield once again, this time about his personal life. He was married, and his wife’s name was Lillian. They had a son, Nathan, who goes by “Sonny.” Like his father, Sonny Kleinfield is a writer. I discovered he is a writer for the New York Times. Lillian Kleinfield died at age 88. She died in 2000, 15 years ago. In cleaning out the family home in Fair Lawn after her death, I believe Sonny found the treasure trove of pins and placed them on eBay. Without also including the two pins relating to his father, all we would know is that large PM10 pins were made of both baseball players and auto racers.

Sometimes I think I am chasing ghosts. Maybe they are chasing me.

[Update: I Found Him!]

I should have realized sooner that if there was an answer to who made the large PM10 pins, after I established the likely connection to Motor Speedway Specialties, the answer would appear through something auto racing related. Even after I posted the column, I kept following links about racing. I discovered a website “3wide” that posted old racing photographs; its name is based upon a racing term involving three cars leading the field, each in its own lane. The cars are racing down the track “three across” or “three wide.” A few clicks and I found the Holy Grail that I had been seeking.

A person named “Russ Dodge” submitted an old photograph to the website. The photograph was dated 1961. But the photograph did not depict racers, but a souvenir store. It shows a smiling couple, appearing to be in their early 40s, behind the counter of their store. Beneath the photo is a statement that says the photograph is not to be presented or posted without permission of the photographer or photographer’s family. The photograph itself is not as important as the information about it. Mr. Dodge wrote the following story that was posted beneath the photograph.

“Always a Tough Decision What to Buy Next”

“Many photos, decals, and novelty racing souvenirs in my collection were purchased from Jeanne and Al Otto’s novelty stand at the Flemington Fairgrounds. Each week it was a fun task as a young teen to decide whether to buy a decal, a souvenir of some type or an Ace Lane Sr., John Reilly, or Virgil Plum photo of a ‘Flemington Regular.’

The Otto’s were friendly people and displayed great patience as young potential customers carefully surveyed their inventory for something new each week. They always had the ‘neatest stuff’ and besides from also having stands at Old Bridge and other speedways, they operated a wholesale business called Motor Speedway Specialties Co., supplying other speedway novelty stands across the country.

Ironically, the ‘choosing experience’ returned for me some 25 years after my first purchase. In the early 1980s I managed the novelty stand at Bridgeport Speedway. One of my suppliers was, you guessed it, Motor Speedway Specialties Co. then being managed by Mrs. Otto and basically selling off the old remaining stock from their glory days. How thrilled and lucky I was to be able to buy the original ‘stuff’ I didn’t buy in my youth!

Thanks for listening.

Senior Moment by Russ Dodge”

On November 9, 2012 a visitor to the website offered this comment on the photograph and accompanying story submitted by Mr. Dodge:

“Great memories here! I wish I still had my plastic helmet and goggles. I still have some photos and a Tasnady button.”

Records indicate that Al Tasnady was a stock car racer from Flemington, NJ who raced mostly on dirt tracks.

Where do I begin? I am gratified to learn that the maker(s) of the large PM10 pins were remembered as “friendly people” who helped young collectors. While I was not into racing, then or now, I would have bought up all of their baseball pins if given the opportunity to do so. I feel guilty that I opined these nice people might be tax cheats in their younger days. What this new information taught me was that the racing pins were not sold to race track owners, but to the operators of novelty stands located near the race tracks. And the “wholesale only” description was not completely accurate. Obviously they sold their items retail at stands they operated at nearby race tracks.

So it wasn’t “Peter and Petunia Pinmaker,” but “Al and Jeanne Otto.” On behalf of sports pin hobbyists who collect your creations 50-60 years after you made them, we thank you most sincerely for providing us with so much enjoyment. Al and Jeanne, I have been looking to thank you for a long, long time.

![Image[2]](https://baseballpinbackbuttons.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/image2.jpg?w=584)

Who could not root for a guy named “Hoop”?

Who could not root for a guy named “Hoop”? Bobby Marshman was one of the stock car drivers who raced at the Indy 500.

Bobby Marshman was one of the stock car drivers who raced at the Indy 500.

Gouevia’s helmet doesn’t look like it would provide much protection in an accident.

Gouevia’s helmet doesn’t look like it would provide much protection in an accident.